Scholarly Pursuits

Scholarly Pursuits Lethal Remedies

Lethal Remedies Victorian San Francisco Stories

Victorian San Francisco Stories Madam Sibyl's First Client: A Victorian San Francisco Story

Madam Sibyl's First Client: A Victorian San Francisco Story Uneasy Spirits: A Victorian San Francisco Mystery

Uneasy Spirits: A Victorian San Francisco Mystery Dandy Detects: A Victorian San Francisco Story

Dandy Detects: A Victorian San Francisco Story Pilfered Promises

Pilfered Promises Dandy Delivers

Dandy Delivers Kathleen Catches a Killer

Kathleen Catches a Killer Violet Vanquishes a Villain

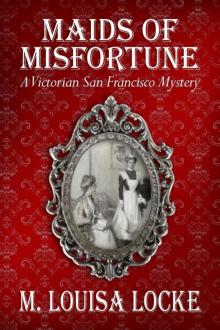

Violet Vanquishes a Villain Maids of Misfortune: A Victorian San Francisco Mystery

Maids of Misfortune: A Victorian San Francisco Mystery